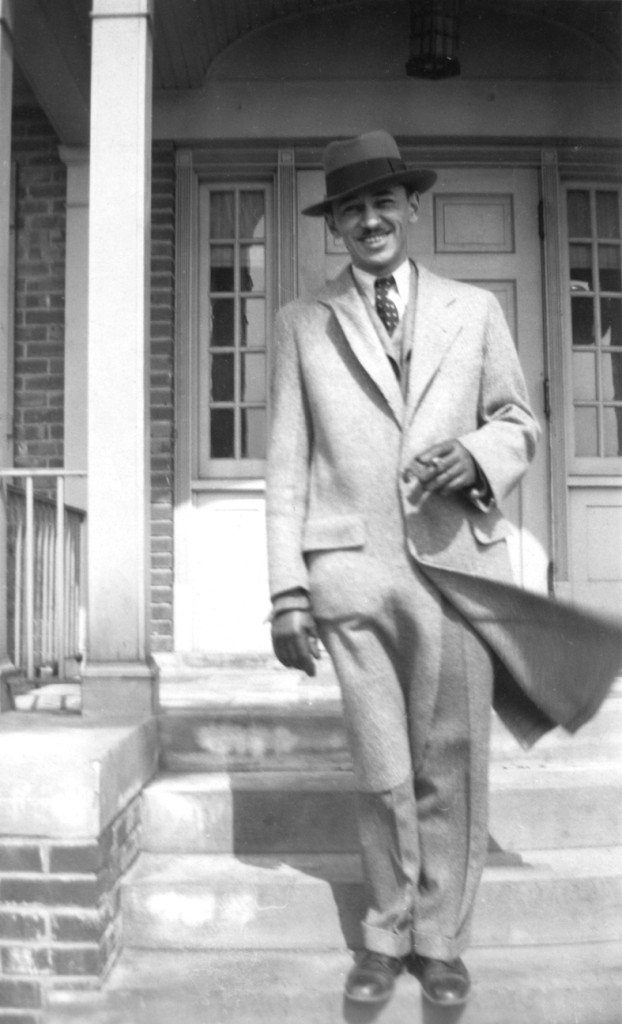

Photo: Morris Wattles, 1928

We know the definition of a primary source: an artifact, document, recording, or other source of information that was created at the time under study. However, this simple definition cannot convey the emotions we experience when we hold a piece of real history in our hands.

As a graduate student I had to evaluate the historic value of letters written by a textile worker during the late 1800s. This collection of handwritten documents is housed at the Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University’s Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs. Anne had worked in a series of mills after her husband was disabled in an accident. Her letters revealed deplorable working conditions, poor pay, and her incredible efforts to earn enough money to feed her family and keep a roof over their heads. The value of the primary source was the historic content expressed in Anne’s own hand. However I felt personally connected with her through those sheets of paper we both had held. I realized that a chemist might still detect her DNA on the envelopes. It was powerful personal experience.

I felt a similar reaction this week when I read TROY, a speech penned by Morris Wattles and delivered on February 22, 1920 at a meeting of the Oakland County Pioneer and Historical Society. Morris was the grandson of Alexander Wattles, a pioneer who purchased land in Troy in 1837.

In the first paragraph Morris wrote, “But only those who have seen the Township of Troy during the last year,- its acres upon acres of subdivisions, city lots, and street markers, its acres bare of trees, producing grain and feeding flocks and cattle- only these people can have any possible conception of the great changes that have taken place during the last one hundred and one years. For we are told, it was one hundred and one years ago on the 12th of February that the first lands in Troy were purchased from the government.”

I was immediately struck by Morris’ view of his community so changed from the wilderness his grandfather knew. Troy Township’s population in 1920 was only 2,520 souls, yet Morris saw “acres and acres of subdivisions.” Like any good Troy resident, he also commented about the roads. “. . . there is a stretch of the Niles Road (Livernois) just south of Council Corners (Maple Road) where, during the extremely wet seasons, one is badly shaken from riding over the remnant of a corduroy road.” A corduroy road was made when rough logs were laid across muddy paths so people, oxen, and wagons didn’t sink into the muck. However, Morris also proudly noted the improved roads of his era. “At present there are in the township six miles of cement road and ten miles of state gravel. The other roads are fairly good country roads, with firm gravel beds.”

It is February 2016– exactly 96 years have passed since Morris wrote the speech that I hold in my hands, and 200 years since the federal government sold the first parcels in Troy on February 12, 1819. Once again I feel a personal connection through a primary source and I am awestruck by Morris’ poetic and prophetic conclusion. “At the present rate of growth it will not be long before the fair fertile fields of a rich agricultural district will be buried under pavement and sidewalk, and the brave adventurers who first walked the leafy avenues will be utterly forgotten by those who will tread the avenues of asphalt.”